| UCLA Library Special Collections |

|

|

A

craze for all things Turkish swept Europe in the 1700s,

probably as a result of the first European translation of

the Arabian Nights (into French, by Antoine Galland

in 1704-17, and then into English in 1706). Europeans were

enthralled by the tales of sultans, slaves and harems; suddenly

turbans, satin slippers, harem pants, Turkish-style gowns

and Turkish carpets were the rage. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s

Letters went into 23 editions between 1763 and

1800. The fad affected music, too. Mozart wrote two “Turkish”

operas – The Abduction from the Seraglio

(premiered in Vienna in 1782) and Zaide.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

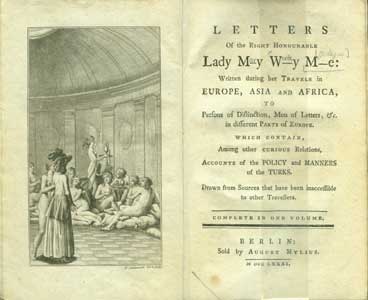

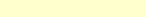

Lady

Mary Wortley Montagu

(1689-1762)

When her husband was

appointed Ambassador to Turkey in 1716, Lady Mary decided

to travel with him, a scandalous decision for a woman at

the time. She was the first to write about the mysteries

of the seraglio, declaring that

|

Lady Mary Wortley

Montagu. Letters … Written during her Travels

in Europe, Asia, and Africa to Persons of Distinction, Men

of Letters, &c. … which Contain … Accounts

of the Policy & Manners of the Turks. Berlin: Sold

by August Mylius, 1781. |

| Turkish

women had more freedom than English women. She was also broad-minded

enough to have her own children “engrafted” with

the smallpox virus, a practice she learned from Turkish medicine

women, and took this knowledge back to England with her -

seventy years before Jenner’s vaccination. |

Emmeline

Lott. The English Governess in Egypt: Harem Life in

Egypt and Constantinople. London: Richard Bentley,

1866.

Miss Emmeline Lott

accepted a two-year appointment, in 1863, as governess to

the five-year old son of Ismael Pacha, the Viceroy of Egypt,

in 1863. She lived in the harem, where she was responsible

for the education (and life) of her young charge. She endured

“fever, cholera and poor diet,” and found the

whole experience “lewd” and offensive. Her books

were bestsellers.

|

|

|

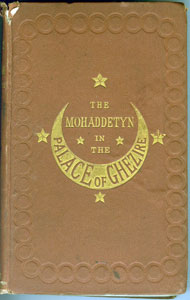

Emmeline

Lott. Nights in the Harem. London: Chapman and

Hall, 1867.

A book of tales à

la Arabian Nights, written, says Lott “to show

how his Highness the Grand Pacha and his Highnesses …

are accustomed to pass their evenings in the Viceregal Odalisk.”

|

|

|

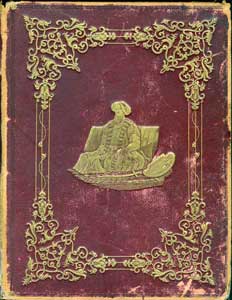

Julia Pardoe

(1806-1862)

Miss Pardoe was a prolific poet,

novelist and travel writer. This attractive book about her

trip to Constantinople with her father, in 1835, achieved

considerable success. |

Julia Pardoe. The

Beauties of the Bosphorus. London: Published for the

proprietors by G. Virtue, 1838. |

THE

HAREM

For Westerners, the

harem was a symbol of passion and forbidden sensuality.

Fascination with Eastern exoticism intensified in the nineteenth

century as painters like Delacroix and Ingres covered their

canvases with voluptuous odalisques. Women travelers had

an advantage here, as only they had access to the opulent

Turkish baths and seraglios. By the 1840s, every serious

female travel writer visited a harem and wrote about it.

Opinions varied; not everyone agreed with Wortley Montagu

about the sexual freedom of Turkish women. Harriet Martineau,

for example, described them as “the most injured human

beings I have ever seen … if we are to look for a

hell upon earth, it is where polygamy exists.”

|

The Harem by

John Frederick Lewis (Victoria and Albert Museum) |

wilder

shores exhibit home |

europe

| russia

| turkey

| the

middle east | india

and the far east | africa

| the

americas | credits

©

2007 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights

reserved. |

|

Wilder

Shores is organized geographically, loosely following the structure

of Barbara Hodgson’s book No Place for a Lady: Tales of Adventurous

Women Travelers. (Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2002). The exhibit features

books and manuscripts, both by and about, women who traveled to these

regions:

|