| UCLA Library Special Collections |

|

|

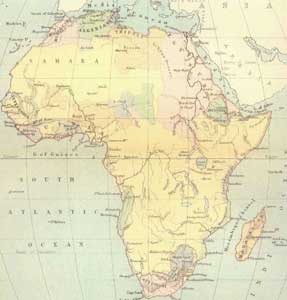

NINETEENTH-CENTURY

LADY TRAVELERS IN AFRICA Women

travelers to Africa were true explorer-adventurers, willing

to undertake long, dangerous journeys to remote places at

considerable risk to themselves. In doing so, they saw themselves

as equal participants in the tradition of nineteenth-century

male exploration. Kingsley spoke of “the school of

travelers of which Du Chaillu, Dr. Barth, Joseph Thomson

and Livingston are past masters and of which I am a humble

member.” These women’s achievements were considerable,

most notably, Sheldon’s exploration of Lake Chala,

on the slopes of Mount Kilamanjaro, and Kingsley’s

surveys of the Ogowé and the Rembwé Rivers

in West Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| May

French Sheldon (1848-1936)

Sheldon, born in Boston,

is the most eccentric lady traveler. She explored the East

African desert in an elaborate wicker palanquin (of her

own design), wearing gowns (and sometimes a blonde wig),

with enough baggage to require a retinue of 100 porters.

She was also the author of a best selling novel, Herbert

Severance, and the translator of Flaubert’s Salammbo.

Her work on the previously unexplored Lake Chala led her

(along with Bird and Marsden) to be one of the first women

elected into fellowship of the Royal Geographic Society

in 1892.

|

May French Sheldon.

Sultan to Sultan: Adventures among the Masai and other

tribes of East Africa. London: Saxon & Co., 1892.

Frontispiece. |

|

Mary Gaunt (1872-1942)

Mary Gaunt, novelist and travel writer,

is the most famous Australian lady traveler. She swung her

way through the Gold Coast of Africa in a hammock, carried

by native men. Her particular interest was describing the

domestic life and social customs of the African peoples

she encountered. Like Mary Kingsley, she was critical of

missionary methods and of pre-War British imperialist attitudes.

|

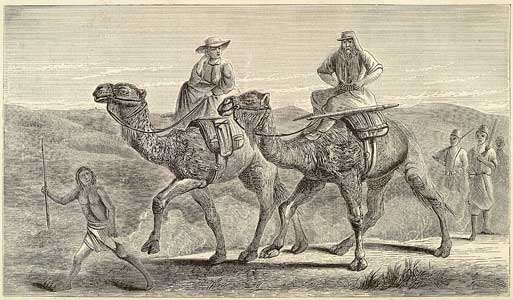

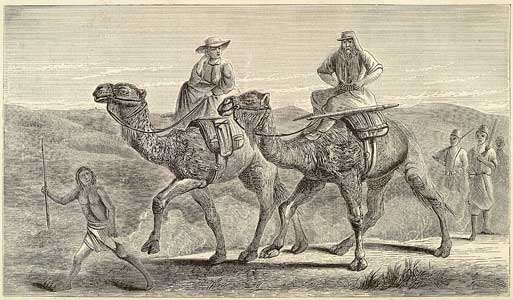

| Florence and Samuel Baker

– ‘Lovers on the Nile’

Florence von Sass was a seventeen-year

old, about to be sold into bondage at a slave market in

Hungary, when recently widowed English explorer, Sir Samuel

Baker, rescued her. She participated in both of his African

expeditions to Abyssinia (Ethiopia), one to find the source

of the Nile, and the second to thwart the slave trade. Though

they traveled as man and wife, they did not marry until

their return to England in 1865; this hint of scandal caused

Florence to be unjustly ostracized by some members of London

society. She was a loyal, brave and resourceful partner.

Samuel wrote that she had “a share of sang-froid admirably

adapted for African travel. Mrs. Baker is not a screamer.”

|

Illustration from Samuel

Baker,Exploration of the Nile tributaries of Abyssinia.

(London: Macmillan and Co., 1867). |

|

Mary

Kingsley. West African Studies. London: Macmillan

and Co., 1899. |

Mary Kingsley

(1862-1900)

Kingsley, insisting that “you

have no right to go about Africa in things you would be

ashamed of at home,” waded through West African swamps

and rivers in Victorian drawing room dress. She made two

trips to Sierra Leone where she became the first westerner

to survey the upper reaches of the Ogowé River. She

was also a self-educated naturalist who discovered several

unknown species and a dedicated spokesman on behalf of tribal

Africans.

|

KIDNAPPINGS

ON THE BARBARY COAST

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth

centuries, the Barbary pirates (based in Algiers and Tunis)

terrorized the seas surrounding northern Africa and the

shores of Europe opposite. At the height of their powers,

in the mid-seventeenth century, they carried off the entire

Irish town of Baltimore; 20,000 slaves were said to be imprisoned

in Algiers alone at the time. Although piracy declined somewhat

in the eighteenth century, kidnapping by Corsairs remained

a risk of sea travel in these regions, especially for women.

Marsh was kidnapped in 1756, and in 1776, Aimée Dubucq

de Rivery, the “French Sultana,” mother of Sultan

Mahmoud II, was abducted from a ship sailing from Nantes

to Martinique (described by Lesley Blanch in her book, The

Wilder Shores of Love). Of those taken captive, the

rich were frequently allowed to redeem themselves; the poor

were condemned to slavery.

|

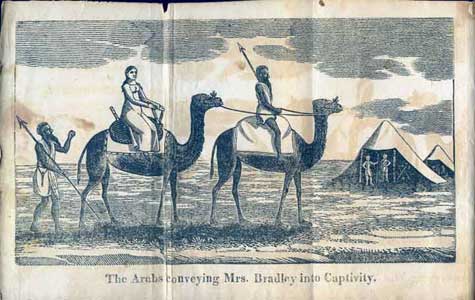

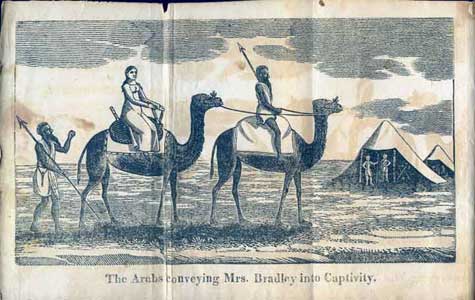

Eliza Bradley. An

Authentic Narrative of the Shipwreck and Sufferings of Mrs.

Eliza Bradley. Boston: James Walden, 1820. |

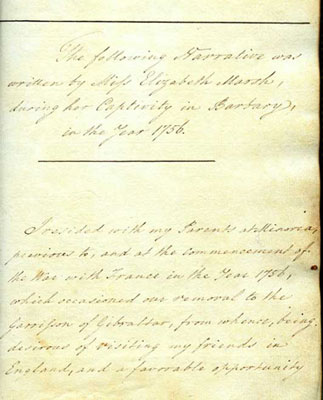

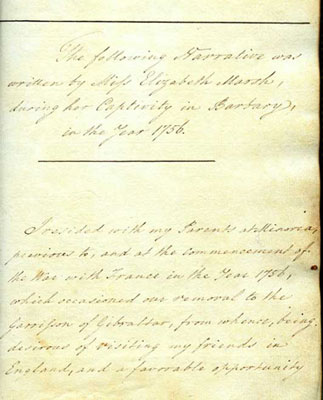

Elizabeth Marsh

(Mrs. Eliza Crisp). Narration … of her captivity

in Barbary, in the Year 1756. Manuscript.

[click

on image to enlarge]

|

A captivity narrative

by a middle-class Englishwoman, Elizabeth Marsh, whose ship

was attacked by Corsairs in 1756. She was taken to Morocco

where the Imperial Prince asked her to join his seraglio.

Like Bradley, she was fortunate enough to be ransomed by

the British government some months later.

|

wilder

shores exhibit home |

europe

| russia

| turkey

| the

middle east | india

and the far east | africa

| the

americas | credits

©

2007 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights

reserved. |

|

Wilder

Shores is organized geographically, loosely following the structure

of Barbara Hodgson’s book No Place for a Lady: Tales of Adventurous

Women Travelers. (Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2002). The exhibit features

books and manuscripts, both by and about, women who traveled to these

regions:

|