Picturing |

|

hildhood |

Picturing |

|

hildhood |

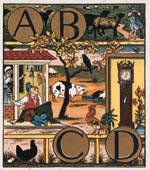

Fig. 2 Walter Crane, illustration from The Alphabet of Old Friends, 1874 (cat. no. 69).

hildren's literature emerged as

a distinct and independent genre only a little more than two centuries ago.

Prior to the mid-eighteenth century books were rarely created specifically

for children, and children's reading was generally confined to literature

intended for their education and moral edification rather than for their

amusement. Religious works (see cat. nos. 7, 8, 14), grammar books, and

"courtesy books" (which offered instruction on proper behavior)

were virtually the only early books directed at children. In these books

illustration played a relatively minor role, usually consisting of small

woodcut vignettes or engraved frontispieces created by anonymous illustrators.

hildren's literature emerged as

a distinct and independent genre only a little more than two centuries ago.

Prior to the mid-eighteenth century books were rarely created specifically

for children, and children's reading was generally confined to literature

intended for their education and moral edification rather than for their

amusement. Religious works (see cat. nos. 7, 8, 14), grammar books, and

"courtesy books" (which offered instruction on proper behavior)

were virtually the only early books directed at children. In these books

illustration played a relatively minor role, usually consisting of small

woodcut vignettes or engraved frontispieces created by anonymous illustrators.

Still, some exceptional works were published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which served as precedents for later genres of children's literature. An early example of a book devoted to children's games is the 1657 Les jeux et plaisirs de l'enfance (The games and pleasures of childhood; fig. 4; cat. no. 4). Produced for and dedicated to children, it is notable not only for its subject but also for its numerous engravings after artist Jacques Stella. Still, the unnatural attitudes of the children's bodies are indicative of the contemporary conception of children as miniature adults.1

Another important precursor was John Amos Comenius's Orbis Sensualium Pictus (The visible world in pictures, 1658). An encyclopedic assemblage of captioned illustrations of the natural world, it is regarded as the first picture book for children. Comenius was an educational reformer, and his book was also innovative in its recognition that there are fundamental differences between children and adults. A forerunner of the illustrated schoolbook, it remained popular in Europe for two centuries and was published in numerous languages and editions (see fig. 1; cat. nos. 5, 6, 11, 13).

Alphabet books exemplify one of the earliest uses of pictures in instructional books for children (see fig. 2; cat. nos. 33–77). From the sixteenth until well into the eighteenth century children learned their alphabets by studying hornbooks (see cat. nos. 33, 38, 39, 50), wooden paddles with inscribed alphabets that were often combined with religious writings such as the Lord's Prayer. Out of the hornbook tradition developed the more pictorial battledore (see cat. nos. 41, 45, 47, 54, 56, 58, 59), a folded piece of cardboard with an illustrated alphabet, named after a traditional game in which hornbooks were used as paddles. The battledore endured until the mid-nineteenth century. By the early nineteenth century other types of games with illustrations were developed for teaching ABCs as well as math, grammar, and science (see fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3 Alphabet of carved letters in carved ivory box, c. 1800 (cat. no. 35). |

Fig. 4 Jacques Stella, illustration from Les jeux et plaisirs de l'enfance (The games and pleasures of childhood), 1657 (cat. no. 4). |

One of the most enduring genres of fiction, fables (see cat. nos. 15–32) were initially read in Latin in the classroom rather than for amusement at home. The stories attributed to Aesop (supposedly a Greek storyteller of the sixth century B.C. but almost certainly a legendary figure) were among the most frequently published and illustrated (see figs. 5, 6). Aesop's Fables was published in its first English translation by William Caxton (c. 1422–91) in 1484. It soon became one of the most popular illustrated books for children, though in many early editions there was little attempt to adapt the stories to make them easier for children to understand and relate to.2

|

Fig. 5 Anonymous artist, illustration from Fabulae Centum, by Gabriel Faernus, 1564 (cat. no. 15). |

Fig. 6 Stephen Gooden, illustration from Aesop's Fables, 1936 (cat. no. 31). |

Return to top of essay | Return to top of section | Go to corresponding section of Checklist of Exhibition

|

Fig. 7 William Nicholson, illustration from An Alphabet, 1898 (cat. no. 73). |

Fig. 8 Anonymous artist, illustration from The Child's Fairy Library, 1837 (cat. no. 163). |

ew attitudes toward children and their education

began to develop in the late seventeenth century, when many educators appealed

for greater consideration of children's distinctive needs and when the notion

of pleasure in learning was becoming more widely accepted.3 Most indicative of this evolution of

ideas are the writings of philosophers John Locke (1632–1704) and Jean-Jacques

Rousseau (1712–78). In 1693 Locke wrote in Some Thoughts Concerning

Education that "children should be treated

as rational creatures. . . . They must not be hindered from being children,

nor from playing and doing as children, but from doing ill."4 Rousseau regarded childhood

as a pure and natural state—one distinct from adulthood—and believed that

a central goal of education should be to preserve the child's original nature.

He also believed that it was essential for teachers to see things as children

do.5 The writings

of Locke and Rousseau influenced British educators, and their ideas ultimately

led to a more humane approach to education in which enjoyment was considered

an aid to learning.

ew attitudes toward children and their education

began to develop in the late seventeenth century, when many educators appealed

for greater consideration of children's distinctive needs and when the notion

of pleasure in learning was becoming more widely accepted.3 Most indicative of this evolution of

ideas are the writings of philosophers John Locke (1632–1704) and Jean-Jacques

Rousseau (1712–78). In 1693 Locke wrote in Some Thoughts Concerning

Education that "children should be treated

as rational creatures. . . . They must not be hindered from being children,

nor from playing and doing as children, but from doing ill."4 Rousseau regarded childhood

as a pure and natural state—one distinct from adulthood—and believed that

a central goal of education should be to preserve the child's original nature.

He also believed that it was essential for teachers to see things as children

do.5 The writings

of Locke and Rousseau influenced British educators, and their ideas ultimately

led to a more humane approach to education in which enjoyment was considered

an aid to learning.

By the early eighteenth century interest in children's literature (and a rise in literacy) led to new markets and a flourishing of new publishers, particularly in England. Innovations in typography and printing allowed greater freedom in reproducing art through engraving, woodcut, etching, and aquatint, although illustrators were still largely anonymous and illustrations confined to frontispieces.

Thomas Boreman was one of the first entrepreneurs to respond to the market with his miniature books entitled Gigantick Histories (1740–43; see cat. no. 79) as well as other illustrated books on subjects such as natural history (see fig. 9). The most important of the early publishers was John Newbery (1713–67). Newbery ran his London bookshop from 1745 to 1767, publishing vast quantities of children's literature of all types as well as a wide range of books on reading, philosophy, and science, most covered in flowered and gilt Dutch paper and enlivened by simple woodcut illustrations (see cat. nos. 82, 105, 131).6 His first children's book was A Little Pretty Pocket Book (1744), and one of the most popular was his 1765 History of Little Goody Two Shoes (see fig. 10; cat. nos. 82, 105, 131), regarded as the first novel written specifically for children (it is said to have been written for Newbery by Oliver Goldsmith).7

|

Fig. 9 Anonymous artist, illustration from A Description of a Great Variety of Animals and Vegetables, 1736 (cat. no. 78) |

Fig. 10 Anonymous artist, illustration from The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes, 1768 (cat. no. 82). |

Other enterprising London publishers who succeeded Newbery were John Harris and John Marshall. In 1807 Harris published the innovative Butterfly's Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast by William Roscoe (cat. no. 108), a nonsensical rhymed tale of insects in the woods, which offered pure fantasy unadulterated by moral lessons. Harris continued to publish more standard didactic works as well as fairy tales and nursery rhymes. Marshall's books were published in a variety of forms, including the first infant's libraries, boxed miniature libraries (see cat. nos. 92–94; ill. p. 6), as well as infant's cabinets, decorated boxes containing small books and pictures (see cat. nos. 96–98, 100). Children's literature at this time ranged from these more expensive editions to the widely published chapbooks, inexpensive pamphlets distributed by peddlers throughout the countryside.

The two most significant genres of eighteenth-century children's literature were the fairy tale and the moral tale. Fairy tales, which had been passed down from generation to generation through oral tradition, were first collected and put into print at the French court of Louis XIV by writers such as the Countess d'Aulnoy, Madame de Villeneuve, and Madame Le Prince de Beaumont. Charles Perrault's 1697 Histoires ou contes du temps passé (Tales of long ago; see cat. nos. 144, 146–48, 150, 192) contain the first written versions of "Cinderella," "Sleeping Beauty," "Red Riding Hood," "Blue Beard," "Hop o' My Thumb," and "Puss in Boots."8 Perrault's versions of these stories have dominated English and American children's literature since the eighteenth century. The frontispiece of his original edition (fig. 11) pictured an old woman telling stories to a group of children, with the inscription Contes de ma mère l'oye ("Tales of mother goose," a French folk expression roughly equivalent to "old wives' tales"). This was the first appearance of the character who would later be associated with nursery rhymes when the Newbery firm attached the name to a collection published under the title Mother Goose's Melody; or, Sonnets for the Cradle (1781; cat. no. 154).

Fig. 11 Anonymous artist, illustration from Histoires ou contes du temps passé, (Tales of long ago), by Charles Perrault, 1698 (cat. no. 144).

Fairy tales, as well as popular adventure tales such as Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719; cat. nos. 115, 121), often engendered criticism in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Sarah Trimmer (1741–1810), a noted author of moral lesson books, denounced "imaginary beings for children" in her 1773 review of Mother Bunch's Fairy Tales.9 Indeed, though numerous chapbook editions of Perrault were published throughout the eighteenth century, they were generally overshadowed by more didactic books that dealt with issues of morality or religion. It was not until well into the nineteenth century that fairy tales came to dominate the children's book market.

Moral or cautionary tales, in which good children were rewarded and bad children were appropriately punished, were generally of less interest with regard to illustrations than were fairy tales. Many were religious tracts written under the influence of Anglican Evangelicals, and they were published in great number throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, by firms such as Newbery and Marshall. The proliferation of editions of such books as Isaac Watts's Divine Songs (1715; see cat. no. 213) testifies to the enduring popularity of works that put religious lessons into a more enjoyable form. Among the most notable women authors of devotional literature or moral tales in England were Trimmer, Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743–1825), and Mary Martha Sherwood (1775–1851).

|

Fig. 12 Anonymous artist, illustration from The Picture Gallery; or, Peter Prim's Portraits of Good and Bad Girls and Boys, 1814 (cat. no. 205). |

Fig. 13 Lydia L. Very, Red Riding Hood, 1863 (cat. nos. 172-173). |

|

Fig. 14 Heinrich Hoffmann, illustration from Der Struwwelpter, 1876 (cat. no. 214). | |

Return to top of essay | Return to top of section | Go to corresponding section of Checklist of Exhibition

Fig. 15 Lothar Meggendorfer, illustration for Die Uhr (The clock), 1907 (cat. no. 300).

Movable parts appeared in scientific books as early as the sixteenth century (see cat. nos. 1–3, 10), but not until the mid-eighteenth century were movable books conceived as entertainment for children or adults. The toy trade also became increasingly important as the children's market grew.10 The harlequinade, a type of novelty book named after theatrical pantomimes featuring the harlequin in a leading role, was invented around 1765 by London bookseller Robert Sayer (see cat. nos. 216–18, 227, 228). Composed of a single sheet of paper with illustrations on flaps that open to reveal another picture below, the harlequinade immediately became immensely popular. Also related to the theater were juvenile drama sheets (see fig. 16; cat. nos. 247, 248, 257, 258, 260), printed sheets of scenery and characters out of which children created their own miniature theaters, the earliest of which date to about 1810.11 Around the same time the London firm of S. and J. Fuller invented the paper doll (see fig. 17; cat. nos. 156, 231, 233, 236, 243). These loosely inserted cutout figures with removable heads were accompanied by stories in verse, the most famous of which was Little Fanny (1810; cat. no. 231). Fuller was also among the earliest publishers of peep shows (see cat. nos. 222, 224, 225, 242, 250, 251), books that open to form a hinged tunnel for viewing, which were inspired by traveling peep shows. Other firms soon joined the scenic book trade, the most notable of which were Dean and Son and the German publishers Raphael Tuck and Ernest Nister. Nister's most important contribution was the dissolving picture book (see cat. nos. 266, 271), in which the sheets were cut horizontally or into a circle so that a new scene could be revealed by pulling a tab.

|

Fig. 16 Anonymous artist, Pollock's Scenes in Cinderella, c. 1876 (cat. no. 258). |

Fig. 17 Cinderella Paper Dolls, 1814 (cat. no. 156). |

Games were common amusements for children in nineteenth-century England, including board games (see fig. 18), card games, and puzzles. Of particular interest were geographical games, a great many of which were produced by members of the Wallis family, leading publishers of children's games from 1775 through the 1830s (see cat. nos. 219, 229, 234, 239, 244, 249). Maps also provided images for puzzles, the earliest of which date to the 1760s (see cat. no. 253).

Lothar Meggendorfer (1847–1925) illustrated, designed, and engineered the most elaborate and intricate movable books of the century, primarily during the 1880s and 1890s. Though he was also a popular magazine illustrator, his reputation today is based on his mechanical picture books for children, and he is considered the creator of the modern movable toy book. Beginning in the late 1880s and through the 1890s, his books enjoyed great popularity and were published in a variety of editions and languages. He produced books with movable figures operated by interconnected cardboard pieces sandwiched between sheets of paper, transformation pictures with interchangeable segmented parts, books with pop-up designs, and large unfolding books such as his 1899 Das Puppenhaus (The dollhouse; cat. no. 298). The technical wizardry of these books remains unequaled (see figs. 15, 19; cat. nos. 281–300).

World War I brought an end to the publication of movable books and their importation to England from Germany, and the lack of fine printing facilities in England and the United States led to a decline in the movable book trade. The emergence of the pop-up book came after the war, however, and this simplified version of its nineteenth-century predecessor has endured throughout this century.

Return to top of essay | Return to top of section | Go to corresponding section of Checklist of Exhibition

he nineteenth century witnessed the institutionalization

of the idea of childhood as a period distinct from adulthood12 and as a time to be enjoyed, at least

by prosperous middle-class Victorians. During the latter half of the century

many of the classics of children's literature in English appeared, including

Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Louisa May

Alcott's Little Women (1868–69), Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure

Island (1883), Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884),

and Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book (1894). This period also saw the

emergence of the picture book, in which the illustrations—and the artist's

vision—were at least as important as the text. No longer anonymous, artists

were aided by technical advances in printing and a growing middle-class

market for books.

he nineteenth century witnessed the institutionalization

of the idea of childhood as a period distinct from adulthood12 and as a time to be enjoyed, at least

by prosperous middle-class Victorians. During the latter half of the century

many of the classics of children's literature in English appeared, including

Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Louisa May

Alcott's Little Women (1868–69), Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure

Island (1883), Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884),

and Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Book (1894). This period also saw the

emergence of the picture book, in which the illustrations—and the artist's

vision—were at least as important as the text. No longer anonymous, artists

were aided by technical advances in printing and a growing middle-class

market for books.

Late in the eighteenth century illustrations by Thomas Bewick (1753–1828; see cat. no. 22) and William Blake (1757–1827; see cat. no. 109) began to appear in British children's books, laying the foundation for the practice of commissioning well-known artists to illustrate texts. Still, such high-quality illustrations remained the exception rather than the rule. Until the mid-nineteenth century most books were printed in black-and-white, primarily in the medium of wood engraving, with the only color provided by the laborious and expensive process of hand-coloring. After mid-century color printing was prevalent in children's books, though many artists preferred the more reliable methods of black-and-white printing until the 1870s (see fig. 22; see cat. nos. 315, 331).

English caricaturist George Cruikshank (1792–1878) made some of the most influential illustrations of the century when he created etchings for the 1823 German Popular Stories (see fig. 23, cat. no. 302), the first English translation of the celebrated collection of folk tales published in German several years earlier by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. William Thackeray declared Cruikshank's illustrations to be "the first real, kindly, agreeable and infinitely amusing and charming illustrations in a child's book in England."13 Cruikshank continued to influence the genre of children's books with his illustrations for Charles Dickens's novels as well as his retellings of favorite tales to emphasize his temperance beliefs, published in the 1850s (see cat. nos. 167–69, 174).

|

Fig. 21 Richard Doyle, illustration from In Fairyland, by William Allingham, 1870 (cat. no. 317). |

Fig. 22 George Cruikshank, illustration from Jack and the Beanstalk, 1854 (cat. no. 169). |

|

Fig. 23 George Cruikshank, illustration from German Popular Stories, vol. 1, 1823 (cat. no. 302). | |

In the second half of the nineteenth century technical and artistic innovations led to the emergence of children's book illustration as a major artistic genre. Richard Doyle (1824–83), who contributed illustrations and political caricatures to the British comic journal Punch in the 1840s and 1850s, later became famous for his pictures of elves and fairies in such elaborate works as William Allingham's In Fairyland (1870; see figs. 20, 21; cat. nos. 317, 345).14

The greatest advances in color printing came with the wood engravings of Edmund Evans and his development of the toy book in the mid-1860s. These thin picture books consisting of eight pages, each printed on only one side, between stiff paper covers, had existed since the beginning of the Victorian era and were published in great numbers by Dean and Son, Routledge, and other firms, but usually without the participation of notable illustrators. Evans succeeded in engaging such major artists as Randolph Caldecott (1846–86), Walter Crane (1845–1915), and Kate Greenaway (1846–1901), engraving and printing the books himself and working with publishers for distribution.15

Each of these artists brought a different style to the Evans books. Crane was influenced by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement as well as by Japanese prints. He illustrated a variety of toy books for Evans, including alphabet books (see fig. 2; cat. no. 321), fairy tales (see fig. 24; cat. nos. 322, 324), and nursery rhymes (see cat. no. 323), most published by Routledge before 1876.16 Caldecott took inspiration from English caricaturists Cruikshank, William Hogarth, and Thomas Rowlandson, and the stories he illustrated consisted primarily of traditional English tales and nursery rhymes (see cat. nos. 339–41, 350, 351). Greenaway—who gained extraordinary popularity with the publication of her first children's book, Under the Window (see fig. 25; cat. no. 330), in 1878—remained adored by the public as well as by influential critic John Ruskin. Often acting as both author and illustrator, she is best known for her idealized illustrations of children in characteristic bonnets and quaint costumes in picturesque settings recalling the English countryside (see cat. no. 338, 342, 343, 346). Books illustrated by these artists were also tremendously popular in the United States, whose own publishing industry had not achieved the high technical standards reflected in English picture books of the period. Evans dominated the industry until his death in 1905, when commercial wood engraving was replaced by photographic reproduction processes.

|

Fig. 24 Walter Crane, illustration from Beauty and the Beast, 1875 (cat. no. 326). |

Fig. 25 Kate Greenaway, illustration from Under the Window, 1878 (cat. no. 330). |

Like Doyle, John Tenniel (1820–1914) had also worked for Punch but is best known as the illustrator of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (see fig. 26) and its sequel, Through the Looking Glass (1872; cat. no. 370). Alice was one of the landmarks of the nineteenth-century fantasy genre, helping to initiate a tradition of fantastical tales with no obvious moral. Working in close collaboration with author Lewis Carroll, Tenniel created illustrations that set the standard for a work that has been interpreted by more than one hundred illustrators since its initial publication (see fig. 27; cat. nos. 369–81).

|

Fig. 26 John Tenniel, illustration from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll, 1866 (cat. no. 369). |

Fig. 27 Barry Moser, illustration from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 1982 (cat. no. 378). Used by permission of the artist. |

In 1880 Carlo Lorenzini (1826–90), under the pseudonym Collodi, wrote The Adventures of Pinocchio (see fig. 28; cat. nos. 382–91), which was first published in English in 1892. Collodi's story originally appeared as a serial in the Italian magazine Giornale dei bambini and is one of the most inventive and complex of nineteenth-century fantasies. Late in the century in France Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel (1851–1913) further refined the art of the picture book with the elaborate color lithographs for the 1896 Jeanne d'Arc (Joan of Arc; cat. no. 364). Some of the most important American book artists, such as Howard Pyle (1853–1911), began as illustrators for the numerous juvenile periodicals that appeared during the Reconstruction era (see cat. no. 392).

Return to top of essay | Return to top of section | Go to corresponding section of Checklist of Exhibition

n this century near-universal literacy in developed countries and technical

advances that have made it possible to produce relatively inexpensive high-quality

illustrated books have contributed to tremendous growth in children's publishing.

Innovations in book printing in the early years of the century, particularly

in the use of photography and four-color processing, led to the development

of the deluxe gift book, which expanded upon the rich tradition of Edmund

Evans. Elaborate watercolors by Edmund Dulac (1882–1953), Kay Nielsen

(1886–1957), and Arthur Rackham (1867–1939) in England, and the

paintings of Maxfield Parrish (1870–1966) and N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945)

in the United States, became the hallmarks of these books, with illustrations

printed on special glossy paper and tipped into the pages. The works of

Rackham, Dulac, and Nielsen varied in style and inspiration. Rackham emphasized

line, using pen and ink with watercolor to create evocative illustrations

for fairy tales and other stories (see fig. 29; cat. nos. 404–7, 428,

429). Dulac's and Nielsen's work was noted for its colorism and influences

drawn from Eastern artistic sources such as Persian miniatures. A notable

example of Nielsen's intricate and exotic style is a suite of watercolor

illustrations for a never-published version of One Thousand and One Nights

(see fig. 30; cat. nos. 410, 412–27). Public

demand for deluxe picture books diminished after World War I. While interest

in Rackham's books persisted, younger artists such as Nielsen, who published

only four books of fairy tales, never achieved such sustained renown.17

n this century near-universal literacy in developed countries and technical

advances that have made it possible to produce relatively inexpensive high-quality

illustrated books have contributed to tremendous growth in children's publishing.

Innovations in book printing in the early years of the century, particularly

in the use of photography and four-color processing, led to the development

of the deluxe gift book, which expanded upon the rich tradition of Edmund

Evans. Elaborate watercolors by Edmund Dulac (1882–1953), Kay Nielsen

(1886–1957), and Arthur Rackham (1867–1939) in England, and the

paintings of Maxfield Parrish (1870–1966) and N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945)

in the United States, became the hallmarks of these books, with illustrations

printed on special glossy paper and tipped into the pages. The works of

Rackham, Dulac, and Nielsen varied in style and inspiration. Rackham emphasized

line, using pen and ink with watercolor to create evocative illustrations

for fairy tales and other stories (see fig. 29; cat. nos. 404–7, 428,

429). Dulac's and Nielsen's work was noted for its colorism and influences

drawn from Eastern artistic sources such as Persian miniatures. A notable

example of Nielsen's intricate and exotic style is a suite of watercolor

illustrations for a never-published version of One Thousand and One Nights

(see fig. 30; cat. nos. 410, 412–27). Public

demand for deluxe picture books diminished after World War I. While interest

in Rackham's books persisted, younger artists such as Nielsen, who published

only four books of fairy tales, never achieved such sustained renown.17

Fig. 30 Kay Nielsen, The Tale of King Yunan and Duban the Doctor, from One Thousand and One Nights, 1917 (cat. no. 410).

Also dating to the early part of the century, books by Beatrix Potter differed in style from the deluxe gift books, and her small, cozy books—designed so that even very young children could comfortably hold them—instead follow the picture book tradition of Caldecott. Her Tale of Peter Rabbit was first privately published by the author in 1901 (cat. no. 398), with a colored frontispiece and other illustrations in black-and-white, but was soon followed by numerous editions with full-color plates (see cat. no. 400).

In the United States early twentieth-century color printing technology made the simple black-and-white illustrations favored by Pyle and his contemporaries seem outmoded. W. W. Denslow's illustrations for L. Frank Baum's Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900; cat. no. 396) included one hundred two-color images and twenty-four full-color plates, making it one of the most elaborate books of its time. Many illustrators continued to explore the possibilities of black-and-white, however. For example, Wanda Gág's creative integration of line illustration and text in Millions of Cats (1928; cat. no. 433) made her the first important American author-illustrator.

The earliest picture books by Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, date from the 1930s and also reflect the importance of the author-illustrator in twentieth-century children's books. Geisel was a former magazine cartoonist, and his preliminary drawings reveal a complex process of merging text and illustration to create his witty and lively "logical nonsense" (see cat. nos. 444–78). Lucille and Holling C. Holling's books of the 1940s evince a nostalgia for preindustrialized America, with rich illustrations and texts focusing on the country's natural resources and on Native Americans' interactions with the environment (see figs. 31, 32; cat. nos. 479–87).

|

Fig. 31 Holling C. Holling, illustration for Paddle-to-the-Sea, 1941 (cat. nos. 480, 481). |

Fig. 32 Holling C. Holling, painted wooden model for Paddle-to-the-Sea, 1941 (cat. no. 480). |

Children's literature today is comparable to popular adult literature in its range and diversity of genres, with books designed for readers at every stage of development, from infancy to young adulthood. The continued vitality of children's publishing, despite competition from a host of newer media, suggests that the illustrated storybook remains unparalleled in its ability to nurture the imagination and to provide both instruction and delight.

|

Fig. 33 Kay Nielsen, The Steward's Tale of the Sultan's Wife's Favorite, from One Thousand and One Nights, 1918-22 (cat. no. 417). |

Fig. 34 Ivan Bilibin, Volga, 1904 (cat. no. 401). |

Return to top of essay | Return to top of section | Go to corresponding section of Checklist of Exhibition

1. See Early Children's Books and Their Illustrations (New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1975), p. 213. Return to text.

2. See Gillian Avery, "The Beginnings of Children's Reading to c. 1700," in Children's Literature: An Illustrated History, ed. Peter Hunt (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 13. Return to text.

3. Gillian Avery notes that there were precedents for the seventeenth-century idea of pleasure in learning and cites early examples of this interest in such works as Roger Ascham's The Schoolmaster (1570); see ibid., p. 11. Return to text.

4. Quoted in Cornelia Meigs et al., A Critical History of Children's Literature: A Survey of Children's Books in English, rev. ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1969), p. 54. Return to text.

5. For a discussion of the origins of the idea of childhood and its relationship to art, see James Seward, The New Child, exh. cat. (Berkeley: Art Museum, University of California, 1996), p. 82ff. Return to text.

6. See S. Roscoe, John Newbery and His Successors, 1740–1814 (Wormley: Five Owls Press, 1973). Return to text.

7. For a discussion of the authorship of Goody Two Shoes, see Mary F. Thwaite, From Primer to Pleasure in Reading, 2d ed. (London: Library Association, 1972), p. 50. Return to text.

8. Perrault's manuscript is in the Morgan Library; see Early Children's Books, p. 111. Return to text.

9. Quoted in Gillian Avery and Margaret Kinnell, "Morality and Levity (1780–1820)," in Hunt, ed., Children's Literature, p. 69. Return to text.

10. See Peter Haining, Moveable Books: An Illustrated History (London: New English Library, 1979), p. 10ff. Return to text.

11. See Eric Quayle, The Collector's Book of Children's Books (London: November Books, 1971), p. 130. Return to text.

12. For a discussion of Victorian views of childhood and literature, see Susan E. Meyer, A Treasury of the Great Children's Book Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983), p. 13ff. Return to text.

13. Michael Patrick Hearn, "Discover, Explore, Enjoy," in Myth, Magic, and Mystery, exh. cat. (Norfolk, Va.: Chrysler Museum of Art; Boulder, Colo.: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1996), p. 8. Return to text.

14. The same illustrations were used in 1884 to illustrate Andrew Lang's Princess Nobody (cat. no. 345). Return to text.

15. Meyer, Children's Book Illustrators, p. 27. Return to text.

16. Crane's contract with Routledge expired in 1876. He went on to work with Evans independently and, from 1875 to 1889, illustrated books in black-and-white by Mrs. Molesworth (see ibid., p. 88). Return to text.

17. See ibid., p. 195. Return to text.

© 1997 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved.